I wrote a couple of posts back that I preferred taking the train. Here is a little vignette showing why. I'm sitting at Termiz train station waiting for my ride to Samarkand. The Dushanbe-Moscow express has just passed by on its 4800km, 3-day journey. Although the Soviet Union imploded 20 years ago, its railway network still trundles on, with trains criss-crossing the former Communist behemoth linking most of its former countries (the Baltics and the Caucasus being the only exceptions). So it is possible in Nukus to hop aboard the Tashkent-Kharkiv train and be directly transported to Ukraine in a few days, crossing three international borders, a journey that has taken me over 7 months in the opposite direction. As a slight aside, the word for train station in the ex-Soviet world is vokzal. Those with more than just a passing knowledge of London may find it oddly familiar, sounding very much, as it does, like the district of Vauxhall. In the 17th to 19th centuries Vauxhall was the site of luxurious pleasure gardens (which may come as a surprise to current inhabitants of the borough) that were emulated throughout Europe, including Russia. When the first train line was constructed in Russia it was just to such a garden, and so was called Vokzal, after which all train stations gained the name.

Soon the Tashkent train that would take me to Samarkand slipped into view and people started climbing aboard. I joined them, and was relieved that I had drawn a low bunk as it would allow me to stash my rucksack in the compartment beneath it. I was sharing my immediate compartment with two middle-aged men and a son in his thirties. Across the aisle from us an imposing matron set up her throne, flanked by her daughter and two grandchildren. She seemed austere at first, until she pulled out a portable boom-box from her handbag and which started blaring Uzbek pop. There wasn't much conversation to begin with until people started pulling out their supplies: bread, tomatoes, cucumbers, tea, salami, mackerel (in a tin), pastries and, of course, vodka. All this was piled high on the creaky table between the bunks. Everyone pitched in and everyone (in our small section of the carriage) was invited. As soon as the vodka started flowing so did the conversation. I can't say I remember much but it certainly beat sitting in a cramped, sweaty bus.

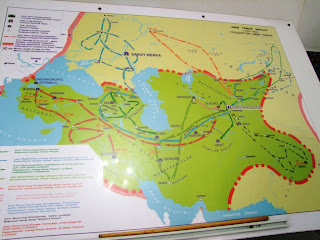

My destination, Samarkand, like Timbuktu, is one of those names that evokes exotic images and fairytale adventures. Samarkand had its brief, but glorious, moment in the sun when it was the capital of Tamerlane's ephemeral empire. Over a 35-year period Timur went from one battle to another, starting from nothing and eventually conquering Central Asia, Iran, Iraq, the Caucasus and doing some damage on Egypt, India and Turkey too. Along with notoriously building pyramids of his vanquished foes' skulls (from 50 to 90 thousand depending on who you read - though to be honest the number is not that important; it was a lot) after conquering Esfahan, Tim collected all the artisans and craftsmen as well as war booty from his conquered dominions and poured them into his capital. Like his European, Gothic contemporaries he wasn't into subtle statements and wanted to cow everyone with the size and grandeur of his monuments. The result were some of the most imposing buildings of all time, including the Ak Saray palace and Bibi Khanym mosque (Samarkand's current architectural symbol, the Registan, was built later), whose aiwans towered up to 40m in height. Unfortunately not much is left of these grandiose buildings as they pushed construction methods to their limits and were unable to withstand the test of time and earthquakes, although recent restoration works have tried to remedy matters.

Although Samarkand is stunning, it has lost the vibrancy that still survives in Bukhara, much of it replaced by wide, Russian boulevards and serial blandness. Nevertheless I found it an interesting place as it is the epicentre of a fascinating Uzbekistani phenomenon. Following the breakup of the Soviet Union the resultant countries looked to cement some sort of national identity (often the constituent nations were in fact artificial constructs, created by the Soviet authorities in a bid to "divide and rule", but more on that in a future post). The leaders of Uzbekistan latched onto Timur as a national Uzbek hero and have created a whole cult of personality around him; streets are named after him, his picture adorns many a wall, and no town worth its salt is complete without a statue of Timur looking purposeful atop a horse or lording on a throne. There are several reasons why I find this strange. Firstly there is the uncritical and highly hagiographic nature of the cult that is sometimes even historically inaccurate. Then there are the various dubious ethical aspects to Tim's character, vis-a-vis his propensity for piling up thousands of skulls of his defeated enemies. Not really the mark of a bloke you want to have a cup of tea with, but I suppose it was part of the mores of the time, so I'll let it pass. But the clincher for me is that he wasn't Uzbek. He was ethnically Turco-Mongol and culturally Turco-Persian, with much of his empire centred on the Persian empire that he had conquered. The Uzbeks didn't even arrive in the region until about 50 years after his death and were in fact instrumental in the dismemberment of his empire. Nevertheless in the highly kitsch Amir Timur museum in Tashkent there is a quote from Islam Karimov, Uzbekistan's president since its very birth in 1991, which states in sufficiently pompous fashion that:

"...if somebody wants to comprehend all the power, might, justice and unlimited abilities of the Uzbek people, their contribution to the global development, their belief in future, he should recall the image of Amir Timur."

If the subject and ramifications were not so serious it would be utterly laughable, much like if Bangladeshis were to consider Napoleon as their national idol. The few Uzbeks that I have queried about the subject seem a bit sheepish about the subject and say they haven't really thought about the subject much, but that Amir Timur was "a great man".

P.S. In an ironic twist of fate, Timur's greatest enemy was the Golden Horde of Tokhtamysh that ruled over much of present day Kazakhstan and European Russia. Timur's campaigns ravaged and ultimately weakened the Horde to such an extent that it allowed one of its vassal states to cast off its yoke and in turn conquer its former master. The vassal in question was Muscovy i.e. Russia, which in turn ended up swallowing up the successor states to Timur's once-great empire in Central Asia. Karma?

1 comment:

I suppose the appropriation of Attila by the modern day Hungarians (descendants of some centuries later arrived tribe the Magyars) falls in the same category here.

Post a Comment