My timing, however, is perhaps not as spot on as I would have liked, as the ceasefire between the LTTE (Tamil Tigers) and the government seems to be falling apart as I write this post. There's nothing like being in the middle of a low-level, internal guerrilla war to make your holiday that much more exciting. On top of that I've arrived on a Friday afternoon and need to stick around until Monday to be able to start my visa application process at the Indian embassy. (Generally they give 6 month multiple entry visas every time, but instead I only got a 3 month single entry one. Perhaps they thought I was a trouble-maker or terrorist or something.) Nevertheless I am very glad I made the decision to pop over as my first impressions of the place are very positive. As anybody who has been to India will testify, it can be a trying place: persistent touts, beggars and rickshaw drivers, annoying children, shit on the streets (and I mean literally human excrement) and dodgy traffic to name but a few aspects of travelling in India that can wear away at your patience (and I must admit on a couple of days mine did wear through). Sri Lanka (or at least Colombo) on the other hand seems to be blissfully neat and ordered by comparison: (reasonably) clean streets, rickshaw drivers who actually take no for an answer, polite people, and traffic that actually respects pelican crossings!

Friday, December 30, 2005

Broken Resolution

My timing, however, is perhaps not as spot on as I would have liked, as the ceasefire between the LTTE (Tamil Tigers) and the government seems to be falling apart as I write this post. There's nothing like being in the middle of a low-level, internal guerrilla war to make your holiday that much more exciting. On top of that I've arrived on a Friday afternoon and need to stick around until Monday to be able to start my visa application process at the Indian embassy. (Generally they give 6 month multiple entry visas every time, but instead I only got a 3 month single entry one. Perhaps they thought I was a trouble-maker or terrorist or something.) Nevertheless I am very glad I made the decision to pop over as my first impressions of the place are very positive. As anybody who has been to India will testify, it can be a trying place: persistent touts, beggars and rickshaw drivers, annoying children, shit on the streets (and I mean literally human excrement) and dodgy traffic to name but a few aspects of travelling in India that can wear away at your patience (and I must admit on a couple of days mine did wear through). Sri Lanka (or at least Colombo) on the other hand seems to be blissfully neat and ordered by comparison: (reasonably) clean streets, rickshaw drivers who actually take no for an answer, polite people, and traffic that actually respects pelican crossings!

Sunday, December 25, 2005

Ho Ho Ho!

To evade accusations of being a scrooge I have insinuated myself into the company of Alex and Sarah, a Kiwi couple who I fist met on the bus to Phnom Penh in Cambodia. They continued to follow me through Vietnam, until I finally lost them by crossing over the border into China. But now I have come to repay the compliment. We haven't achieved much, generally just lounging about, chatting and eating (a typical Christmas then) as well as exchanging small, kitschy presents (I got some chocolate money). But it's a nice break from the arduous work of backpacking which I will be resuming in a few days time.

Wednesday, December 21, 2005

Pilgrim's Progress

The temple complex is built in a pleasant little upland plateau surrounded by 7 holy hills. There is a constant stream of buses winding their way up the hillside from the hub town of Tirupati in the valley below. Pilgrims come to pray before a 50cm statue of Lord Venkateswara, an incarnation of the god Vishnu. It is said that any wish made in front of Lord Venkateswara will be fulfilled (no wonder so many people come here). Wishes are, of course, more likely to be successful with an appropriate donation. Usually (i.e. always) this involves money, but also, rather strangely, hair. All around you see people, both men and women, who have given up their hair for their Lord. All this has naturally made the Tirumala temple exceedingly rich (they have a lucrative sideline in providing real hair for rich westerners), which has allowed them to buy over a tonne of gold jewellery for the eponymous statue.

People queue up for hours just to be able to catch a brief glimpse of their idol. I didn't have so much time, or more to the point, so much patience, so I bought myself a VIP ticket whereby, along with a modest donation of 100Rs and a signing of a form declaring my devotion to Lord Venkateswara, I got to bypass most of the queue. That said, it still took me 2 hours to get to the sanctum sanctorum, so I shudder to think how long it must take for those poor pilgrims who pay nothing at all. Apart from the occasional chants of "Govinda! Govinda!" there was, alas, precious little religious harmony or tolerance in the queue, with constant pushing and shoving giving the wait more an impression of a continuous rugby scrum. I'm surprised more people are not injured in the melee. And once at the heart of the temple I had 3 seconds to focus on the little statue 10m down the corridor, almost drowned in flower garlands, before I was roughly manhandled out to make room for the next devotees. Despite this apparent anticlimax I was just fascinated by the whole process. The army of volunteers marshalling the pilgrims and handing out food and assistance; the kitsch stands selling devotional posters of various Hindu deities and other useless trinkets; and the pilgrims themselves, the bald and the soon-to-be bald, barefoot, often silently chanting devotional mantras. And not a single tourist in sight. This was real India: chaotic, esoteric, bizarre, contradictory.

Monday, December 19, 2005

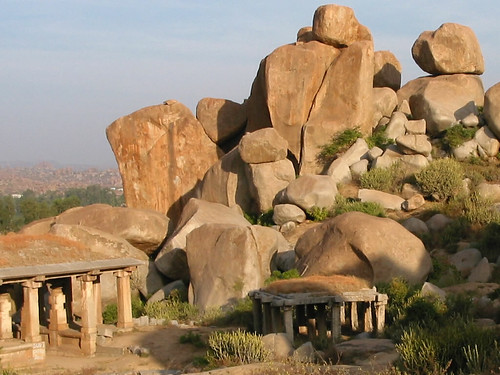

On The Rocks

Friday, December 16, 2005

Too Much Time For Thought

In the 2000 years prior to British rule, the subcontinent had only been united under one flag on two separate occasions: once, under the legendary emperor Ashoka for about 100 years in the third century BC; and then under the Afghan Mughals for 150 years in the 16th and 17th centuries. Apart from these two periods India has been a patchwork of kingdoms, sultanates and confederacies, and even under the empires local rulers had a large degree of autonomy. This all means that the India of today has a dazzling degree of diversity: 18 official (and over a thousand non-official) languages; similar numbers of ethnic, cultural and tribal groups; and on top of that a smorgasbord of gods and religions. It is larger, more populated, more heterogeneous and more complex than Europe, and yet it is one country. No wonder there are half a dozen separatist movements, including the Sikhs in Punjab, the Gurkhas in Sikkim and the Nagas in Nagaland.

Why should India be just one country? what gives these separatist movements less legitimacy than the Tibetans or the Timorese? It seems to me (and perhaps I have too much time on my hands and therefore spend it trying to resolve the world's problems) that the root of many of today's geopolitical problems lies in the carving up of the colonial world after the second world war. When the great powers drew their borders there seems to have been little heed paid to local populations, their feelings, their traditional boundaries or their aspirations for independence. Thus, some ethnic groups were split between several countries without one of their own, like the Kurds (despite having been promised one in 1920 in the treaty of Sevres); other countries became mish-mashes of many disparate ethnic groups, like Nigeria; and some countries were created where none existed before, like Israel. And so the scene was set for many of the bloodiest and most intractable conflicts of the past 60 years. For there is no motivating power as strong, or as irrational, as the Us versus Them mentality of the freedom fighter. Then, depending on which side in any given conflict is more amenable to other countries' views (i.e. how much of their country they will allow to be plundered) the international community will step in whilst, for the television viewers at home, continually paying lip service to Human Rights and the Moral High Ground, seeming to effortlessly distinguish between black and white when in fact everyone is coloured exactly the same shade of faecal brown. Many people in such affected countries see this all as a huge (often Zionist) conspiracy. I'm not so sure. It's probable that it's just initial stupidity followed by self-interested profiteering.

A perfect example of such realpolitik can be found in the miasma that is Iraq today. The Coalition is fighting tooth and nail to Iraq as a single, unified state and not to let it break up into a Kurdish north, Shi'ite south and Sunni middle, despite the fact that this would alleviate many of the existing sectarian tensions. Why is that? Iraq as a country has only existed since 1932 when it was created by the British as an amalgam of three ex-Ottoman regions, which, funnily enough, correspond to the Kurdish, Shi'ite and Sunni regions today. Why not leave it as it originally was? The reason is quite simple. An independent Kurdish state would annoy the Turks (allies of the West) and give legitimacy to their Kurdish separatist movement; a Shi'ite south would fall under the influence of Iran, and we can't let that happen; and the Sunnis in the middle would be pissed off at losing their oil wealth and status. So, for these dubious reasons, a shoddy status quo is maintained and the ordinary people on the ground suffer.

Sunday, December 11, 2005

Spelunking

The two are cave temple complexes carved out of the basalt rock of the hillsides some 2200 to 1200 years ago. Most of the temples are Buddhist, though at Ellora there are Hindu and even Jain temples, and carved horizontally into the hillside. Some of them still contain their carvings and statues, and others yet have managed to retain some of the exquisite frescoes, which must have adorned the entirety of all the caves, portraying the lives of Buddha. But the crowning glory is to be found amongst the Hindu temples at Ellora. This one temple is called the Kailasa temple because it is supposed to represent Mount Kailash, Shiva's abode on earth. The temple was constructed by digging out the rock from the top down (so in actual fact it's not really a cave), so that this whole, monumental building (twice the size of the Parthenon in Athens) is actually made out of one single piece of rock! Something that, as far as I know, has never been done anywhere before or since. The scale of it just takes your breath away, and yet at closer inspection, despite the awesome grandeur, there is also fine attention to detail with smaller sculptures dotted all over the place. It just boggles the mind that something so audacious was even attempted all that time ago, let alone accomplished with such aplomb.

Thursday, December 08, 2005

Party Animal

As for tonight? well, I'm going to have myself a little fiesta on the night train to Aurangabad (8 hours NE of Bombay). I did know a few people here in town, but they left last night for Goa; probably because they didn't want to fork out to get me birthday presents (only joking). But I suppose it's good training spending a birthday on my own, so that I'll be more used to it when I become an old, eccentric bachelor surrounded by stacks of bric-a-brac.

Wednesday, December 07, 2005

Bollywood Or Bust

I had been slightly dreading coming to Bombay, and had been visualising traffic-clogged streets, horribly polluted air, unending noise, pestering touts and generally other such disagreeable annoyances. I was pleasantly surprised to find pleasant, leafy areas in the centre of town, with imposing neo-gothic buildings that remind me of home (only it's rarely 30 degrees with 80% humidity back home). It also makes me think that, although the country was exploited and a lot of its wealth appropriated, there were some positive aspects to British colonialism (especially when I see the buildings of Bombay University, which are much more imposing than those of UCL my alma mater). Another advantage is language. Here, more than anywhere else, English is commonly used in everyday life. Billboards, radio commercials, magazines and shop signs are, more often than not, in English. The younger and more educated section of society especially, seem to almost exclusively use English amongst themselves (I find it fascinating to eavesdrop students' conversations to get a feel for their preoccupations and the little Indian-English idiosyncrasies). Apparently, according to the guy who sold me my digital camera (yay! I've finally bought one, so, once I figure how to turn the thing on, expect to find more piccies in my album in the near future), who was a really nice guy, but then I suppose you would be to someone who's going to hand you over a huge was of cash, the reason for the supremacy of English in Bombay is the profusion of so many people from all over India. And since most people have their own local languages and dialects English becomes the great leveller.

Bombay is also home of Bollywood, India's film-making hub. Indian films are known for their bombastic song and dance routines, lip-synching and atrocious acting. Foreigners sometimes manage to get minor, non-speaking roles in these films and the place I'm staying is a well-known casting ground, though unfortunately I didn't look "foreign" enough for their tastes, and so my aspirations of becoming a Bollywood star have been crushed even before they began.

Thursday, December 01, 2005

Silly Trousers

My travels around Rajasthan have gone on for longer than I had thought (so nothing new there then) as every little town is a gem. After Jaisalmer my next stop was Jodhpur, home of the eponymous trouser worn by posh riding freaks the world over. I was half expecting everyone in town to be wearing them and so was slightly let down by reality, although I did get to see a pair on a guide in the city fort, which, despite the situation being contrived, made me feel better. The fort is one of the most impressive I have seen to date. It is built on an outcrop of rock that juts some 100m above the rest of the city, with huge ramparts that made it impregnable during its 500 year history. The architecture beautiful and very well preserved, and from the battlements you get an unparalleled view, above the soaring hawks and onto the Blue City (as Jodhpur is called) below. It gets its name from the many houses that are painted bright blue. Apparently this used to be the colour of the upper-caste Brahmins, but now everybody seems to have got in on the act. They say the colour keeps the houses cool in the scorching Rajasthani Summers and even repels mosquitoes. Whatever the case, they look beautiful.

From there it was on to Mount Abu, a pleasant hill station retreat, where I could get away from the hustle and bustle of Indian cities. I got to wander around the lovely boulder-strewn hillsides and scout around for wildlife (apparently bears and panthers live in the forests, but all I saw was a chicken). But what really made my visit worthwhile were the Jain temples. Jainism is one of India's religions, though one we hear little about in the west, despite its strong influence on the philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi and Buddhism as well. The Jains are big-time animal respecters (all of them are vegetarians and they usually refuse to wear animal products, such as leather, as well) with the more devout sometimes even wearing face masks so as not to inhale any insects. Anyway, to know more about Jains and Jainism click here. Now I've seen a good many temples, churches and mosques on my travels and so have perhaps become slightly blase, but these just blew me away. The buildings, some almost 1000 years old, are made of white marble, and covered with the most intricate carvings I have ever seen. Almost every inch of free space is taken up with complex geometric patterns, animals or dancing female figures (from viewing the sculptures I have come to the conclusion that Jains like their women busty, see below).

As a slight aside, Jains are sometimes misunderstood in the west because their holiest symbol is the swastika (which, incidentally, can be translated as "little good luck charm"), which is ever present in all their temples and shrines. It's a shame that such an ancient symbol was hijacked by the Nazis and now is inexorably associated with them.

Friday, November 25, 2005

The Ugliest Animals In The World

It was nice to get away from the hustle and bustle of the crowded towns and cities, with their constant noise, smells and pestering. In the whole 3 days we briefly saw two other tourists, but apart from that it was just us and the locals. The latter, especially the women, stand out with their brightly coloured clothes: vivid reds, blues, greens and pinks can be seen from miles away. The whole of Rajasthan, it seems, is only made up of vibrant primary colours: the clothes, the sky, the ground and the havelis (beautifully carved and decorated sandstone houses) all vie for your eyes' attention. Sitting round the campfire after dinner, warming ourselves from the surprising chill of the night and listening to the songs of the camel drivers (we were, of course, obliged to sing as well, so I had to dig out my rendition of Flower Of Scotland again, which is slowly becoming my party piece) was particularly enchanting. It did get rather surreal at one point when one of the drivers started belting out "Country Roads", but then again why not? it's a good song. I also learned three, perhaps not important, but nonetheless interesting, lessons. Firstly it gets cold in the desert at night. Very cold. I knew this beforehand, but didn't quite appreciate it until I got myself a bunged up nose. Secondly that melons grow in the desert. They were almost everywhere: small, yet tasty watermelons. Whenever we got thirsty we could just grab a melon, punch it open and munch away. The number of half eaten melons we left in our wake was really rather shameful. And finally that sand gets everywhere. This I had also experienced before, but I failed to appreciate its effect upon my camera, which, after many years of trusty service, is now officially dead. I am now going to have to bite the bullet and cross the digital divide,something that I had been planning to do only once I returned home. But I suppose you have to adapt to your circumstances.

Tuesday, November 22, 2005

Rats In Rajasthan

The first is the Golden Temple of Amritsar, the holiest of sites for Sikhs. I like to make fun of my Sikh friends saying that they're all big and hairy just to tease them. Though, like all generalisations, there is more than a grain of truth to it and it's fascinating to be in a place full of tall, turbaned men with the bushiest of beards. It's not surprising to read that they were a military force to be reckoned with in their time. Luckily Sikhs are among the most friendly and scrupulously honest people I know. The temple is a large, pristinely white complex surrounding a holy pool containing the eponymous temple sitting in its centre, glinting in the sunlight. Sikhism is a very welcoming and egalitarian faith (if I wasn't such a religious sceptic I might be a Sikh, and I've got a good start already as I've got the beard) and allow everyone in to look around. But better than that, they give you a meal as well! Heaven for a budget traveller. But I get a guilty conscience far too quickly so I doubt I'll be taking advantage of their generosity too much. Seeing the massive dining halls filled with hundreds of people, young and old rich and poor, really gives a sense of community.

The other temple is the Karni Mata temple in northern Rajasthan, commonly known as the Rat Temple due to the thousands of rats that, not only live there, but are regarded as minor deities and are fed and protected in the temple grounds. I was expecting to see a seething carpet of furry bodies, but had to make do with a few scampering little rodents and a circle of squabbling beasties around a bowl of milk. But I still enjoyed myself immensely just watching the travails of the wee blighters, with their little squabbles and curious personalities (they would come right up to my feet and sniff my toes; and then quickly run away again before they were overcome by the smell!).

But now I am in the dessert town of Jaisalmer with my friend Hanka, catching up on the past year and a half since we last saw each other. We spent the day wandering the small streets that surround the imposing, sandstone fort that dominates the city and generally relaxing before we head off on a camel safari into the dessert tomorrow (Hanka is not altogether confident of our survival chances in the barren expanses and has been mentally preparing her last will and testament). But here it's no longer the two-humped Bactrian camel of western China, but single-humped dromedaries, so I'm not quite sure where one is supposed to sit, though I'm sure I'll find out tomorrow.

Sunday, November 20, 2005

Bad Day

Friday, November 18, 2005

Low Walls

"They ate here (pointing), slept there (pointing again), prayed there...that's where they carried out human sacrifices (OK, maybe not the Buddhists)"

How can they tell? it's just walls! Personally I think they're just making it all up and are just as confused about the remains as we ordinary mortals, but just don't want to show it. Well, it must have fooled the boffins at UNESCO at any rate as a couple of the less ruined ruins are world heritage listed. I also had great fun traipsing around the remains, which were blissfully free of tourists (a delightful change to China), and clambering about the fortress that "was stormed by Alexander the Great" and sitting in "Darius's palace".

I have, however, been expecting rather more from the food over here. Not that it's bad, I rather quite like it actually, it's just rather monotonous. My meals invariably consist of roti and dhal, which is bread and lentils (or chickpeas). I have become rather adept at tearing off bits of bread with one hand and using it as a scoop for the dhal, though I'm still loathe to use my thumb as a shovel, not due to any hygiene issue, but I just don't like to get it greasy. My bowels are rejoicing at this simple fare as my stools have improved immeasurably since China, becoming world class specimens, if perhaps with a slightly disturbing shade of orange.

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

Taking It Up The Khyber

Well, seeing as I'm so close, I had to check out the Khyber because you will rarely get to see a pass as legendary as that. Going along it and up to the border, however, is slightly more complex than just hopping on a bus since the pass is in tribal territory. The tribal areas were set aside, during the creation of Pakistan, for the Pashtun tribes who wanted to retain to their traditional way of life. In practice this means that the tribal areas are de facto autonomous and Pakistani law only applies on the road and a short strip on either side. Outside of that area the intricacies of the tribal codes reign supreme and honour-killings over slights of honour are a way of life. Therefore anybody wishing to visit the areas has to get an armed escort as well as the relevant permit.

Once the relevant formalities had been sorted out we set off: me and two other travellers who I had met at the hotel bunched up in the back of a ridiculously small Suzuki taxi, our driver and our guard with his Kalashnikov resting on his lap up front. The pass, in itself, is rather unspectacular (although in some places it does get remarkably narrow), but it is the history of the place and the frontier vibe that are the main draws. Numerous forts, sentry posts and even tank obstacles litter the pass, bearing witness to its strategical importance throughout history. Many of the colonial era military remnants are abandoned, but they are more than compensated by the Pashtun houses, which resemble medieval castles, complete with crenellated battlements and gun slits. Very welcoming. You're not actually allowed to travel all the way to the border if you don't have a visa ("for your own protection"), but from the checkpoint we could clearly see the border town of Torkham and its Afghan twin in the valley below. Whilst peering over at the mountains of Afghanistan we were soon surrounded by a group of Pashtuns (a couple carrying their own Kalashnikovs) who were pleased to see us, not least so that they could practice their English. They explained their aspirations for peace and their own country of Pashtunistan, how they would like to travel abroad and how all the lorries along the road are carrying military supplies for the Americans. I wanted to stay for lunch, but our escort was getting nervous so we had to head back to Peshawar. Our little jaunt has clearly reinforced something that I have learnt during my trip: whatever your image of a place that you form through the media, it is invariably completely false and bears no resemblance to reality; not least because I still haven't been able to find any Peshwari nans.

Saturday, November 12, 2005

Feeling Useless

What impressed me most, however, was the people of the area. Despite having lost their homes, their livelihoods and many members of their families, the legendary Pakistani hospitality was as strong as ever. I actually felt very embarrassed that these people, who were forced to live in tents, were giving me food and shelter when I had come to help them. This is one side of Pakistan that you definitely don't hear about in the media. I have been offered tea and food and shaken more hands in my one week here than in my whole time in the rest of Asia. Sometimes it can be a bit much and people continually come up to me wanting to know my life story: "what country are you belonging to? are you a Muslim? what is your profession? what are your qualifications? are you married?" and so on and so on, hardly pausing to hear my replies, before wandering off. But it's all innocent and fun, and I amuse myself by varying my nationality to see the different responses they illicit (my current favourite is Mexican).

After one and a half days of being passed from one NGO to another and calling various phantom phone numbers, I decided take the hint and leave rather than get in people's way. Perhaps I could have been more forceful in my inquiries, but then again I didn't want to be some morbid disaster tourist. If you would like to help out then there are a plethora of agencies that are doing good work to help the affected, such as the ever-present MSF that I'm sure would accept donations.

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

It's English Jim, But Not As We Know It

I have, however, fled from the Northern Areas to Islamabad; not because it's not nice up there, but because I want to get away from the cold and I need to start applying for my Indian visa (which takes some time). It can get quite annoying the hoops that countries want you to jump through before they will let you in, when all you want to do is spend money in their country. At the moment I'm reading a book by John Simpson in which he talks about how people travelled some 150 years ago. The British refused to have passports and would just arrive at borders and demand to be let in, which they invariably were. Bring back the good old days I say! Either way, I will be back in Pakistan after my tour of the rest of the subcontinent and I'll be more thorough then. Islamabad itself is rather uninteresting as it is one of those 20th century inventions that I'm beginning to really dislike: the designed capital city. They all share certain characteristics that make them rather soulless places, like ridiculously wide boulevards and no pavements; no discernible town centre; and people never seem to live there, they always just work there, or at best reside there. As far as they go Islamabad isn't too bad because although it doesn't have a centre, each of its little districts has a central market which is often lively enough.

Sunday, November 06, 2005

KKH

The road over the Khunjerab pass is the famous Karakoram Highway (or, as it is lovingly known by travellers, the KKH), and it takes two days to get from Kashgar to Sost on the Pakistani side. On the Chinese side the road rises steadily to the windswept Subash plateau that borders Tajikistan and Afghanistan to the west. The landscape is harsh and desolate and life must be tough for the Tajik herders that live up there. The plains are dominated by the great, big meringue that is Muztagh Ata (meaning "Father of Ice" in Uighur), a 7500m behemoth of a mountain. But because the plains are so empty, you lose your sense of perspective and the mountain doesn't look as big as it should. The night is spent in the town of Tashkurgan. It was very late and cold when we got there, so my impression of the town is tainted by my hunger and the onset of frostbite. Needless to say, it was not a highlight.

The next day, after clearing customs and the farcical Chinese bureaucracy, we headed off towards the looming mountains that form the border with Pakistan. The difference, upon crossing the pass, was huge and immediate. Whereas the countryside on the Chinese side was mainly flat with mountains off to the side, in Pakistan the mountains rise straight up from the side of the road making them seem taller, more dangerous, more real. Here a constant battle is waged by man to keep the mountains from consuming the road that was built with so much effort and human sacrifice. All along the route there is evidence of continuous landslides as the mountains try to reclaim the road. I know I've waxed lyrical about many places whilst on my trip, and I have been moved by all of them, but none match the mountains of northern Pakistan for visceral impact. The raw, jagged, primal peaks are the greatest testament to the incredible forces that cause continents to move and collide. Nowhere else in the world can you see such stupendous mountains so closely, or see glaciers descend to within a short walk of the main road. Wherever the road widens only slightly, a village springs up, with sheep and goats scurrying about (although god only knows how the villagers can keep so much livestock as there is barely any grass upon the rocky hillsides). The villagers of these northern areas are fascinating because they do not look at all as one might expect, being sandwiched between the Turkic peoples to the north and the Punjabis and other Pakistanis to the south. In fact, if you were to give them a wash and a change of clothes (and perhaps a shave for some of the men), they could be from pretty much anywhere in Europe. Apparently the people of the Hunza valley are the last remnants of the Kushan empire that ruled the area 2000 years ago, or, according to some, descendants of Alexander the Great's army as he marched through the region some 2300 years ago.

Friday, November 04, 2005

Addenda

But now to the things I left out in my last post. I mentioned that the Chinese are fond of disregarding signs, and this can be particularly annoying when you're sat on a long-distance bus with a crowd of chain smokers and no ventilation. I have therefore developed a new hobby whilst here. I've started demanding that people stop smoking, or when I see them dropping litter (and especially if there is a bin nearby) I tell them to pick it up again. And because they know I'm in the right (especially if they're sitting under a no smoking sign), and generally the Chinese will try to avoid confrontation, they just give an embarrassed smile and put out their cigarettes (or pick up their litter). Sometimes they may try to ignore me, but on a bus there's nowhere to flee and I can get very voluble. The great thing is that they can't really insult me or talk back (which would be the most common response back home) because I just don't understand them and I just keep pestering them. It's great fun and gives me a fantastic feeling of accomplishment.

I also wanted to talk about Chinese writing. Although learning Chinese characters can seem like a daunting task, and in the long term to master the written language is extremely difficult, it is not necessary to master a whole alphabet so one can start picking up characters straight away. Plus it's possible to invent your own little stories to help you memorise the various characters. Some of the more complex characters are combinations of simpler ones and seem to have their own perverse logic, although others just leave me baffled. For example the symbol for "garden" is a combination of the symbols for "money" placed within the symbol for "mouth". Now I still haven't been able to find a Chinese person who can fully explain what putting money into your mouth has to do with gardens. On the other hand, the character for "peace" is made up of the character for "woman" under a "roof" symbol. Now that, to me, makes perfect sense: you can't have peace unless the women are at home. Well, I think I've insulted enough people for one post so I'll stop here. Hopefully my next contribution will be from Pakistan.

Wednesday, November 02, 2005

If You Notice This Notice You Will Notice That It's Not Worth Noticing

As this is my penultimate stop in China this is as good a time as any to give my thoughts and impressions on this immense country I have now spent over 12 weeks in. But first I'd like to digress a little and talk about a topic that has provided me with endless amusement, and more than a little bit of head scratching, whilst criss-crossing this land: signs and notices. All throughout China there are notices exhorting citizens not to spit, not to smoke, to buckle up, to drive on the right and overtake on the left, not to drop litter, to cherish the environment, and to generally be nicer, friendlier and more caring people. The Chinese, however (or at least the vast majority of them), seem to think they apply to other people and duly ignore them. The authorities therefore, when faced with having to translate these signs into English for foreigners, say to themselves "well, if our lot don't bother obeying them, I'm damned if I'm going to spend good money on translating them so that foreigners can ignore them as well". So instead of getting someone who speaks English for the translation they instead turn to free translation tools that can be found on the net. Not only does it seem obligatory for there to be at least one spelling mistake, but the content itself is rather cringeworthy and probably worthy of a book in their own right, but I only noted down some of the choicest examples, and here are some of my favourites.

"It is forbidden to fire the hardcore scenic area" In Wudang Shan.

"No tossing" On a bus window.

"In the building it is forbidden for people with slippery dress" The HSBC building, Shanghai.

"It is not allowed to [...], shit or piss in the park" In a Shanghai park.

"Eggs with fungus and alien vegetables" In a restaurant in Emei Shan (though tempted, I decided to opt for the scrambled eggs and tomatoes instead).

That's enough flippancy for now; back to my summary of China. It's undoubtedly a fascinating country with innumerable sites that evidence its long history (even despite the destruction of the Cultural Revolution). The grandeur of the Great Wall; the beauty of its mountains; its intricate architecture (strictly pre-communist stuff only); and its many, varied ethnic groups, all make China a compelling country to visit. And 3 months isn't even enough to see nearly half the country (future travel itineraries have already been planned). Getting around is relatively simple and it's possible to travel almost anywhere independently with only a limited vocabulary and enough patience. The latter did sometimes fail me, however, as I often found the locals rather uncooperative (and I think I've expressed my opinions about their tourists clearly enough already). Unfortunately this has become the first country in which I've actually lost my temper with someone and raised my voice in anger, something I hate doing and hope won't have to do again. That said, I don't like to criticise people, especially if I don't know the whole story. And in a way I can understand this behaviour. Only 30 years ago the country was completely rural and undeveloped, and the change, in such a short space of time, has been so enormous that the Chinese that were brought up under Mao are probably feeling slightly lost in their own country. The progress that has been achieved, and the ensuing changes to people's lives, in such a short space of time are just mind-boggling. Hopefully, as the people become more accustomed to their new-found prosperity and more educated at the same time, they will become more responsible towards others and their surroundings. If not, then I fear that the country might be heading for some serious problems.

Monday, October 31, 2005

The Hotan Curse

But for me the main draw was Hotan's incredible Sunday market. I haven't seen such a mass of seething, jostling, bustling humanity since Carnaval in Rio, but Carnaval is once a year and the market is every week. This was by far the most thriving and exciting market I've seen on all my travels, and I've seen a fair number of them. There were thousands upon thousands of people pushing and shoving to get through the other thousands of people going in the other direction. Everything was on sale: carpets, sheep, thermal underwear, cool Uighur felt hats, cooking utensils, jackets, barber stalls and, of course, lots of jade. Though, typically enough, they didn't have the one thing that I really wanted: leather mitts. But the jade market was surely the most fun: every man and his dog had a little blanket spread in front of them with chunks of jade ranging from the minuscule to the impossible to lift. And plenty more people would sidle surreptitiously up to me showing me their little pebbles, as if they were hard drugs and it should be kept hush hush. How anybody could make a living from selling jade, when there are 1000 other people selling the exact same useless bits of rock, is beyond me. I developed a hilarious game whereby I'd show some interest in somebody's stone, take it of them to have a look, hand them a pen or other random object and then start to walk off. Often the sellers were too bewildered to realise what was happening until I was a fair distance away. I have to amuse myself somehow! My only quibble was that it is Ramadan and so eating in the market was a big no no, so I had to go back to my hotel (I use the term in the loosest possible sense of the term) early to gobble down some nosh in private.

Apropos of food, all the travellers I met in Hotan got ill whilst there, and I was no exception. I've had a really nasty case of the runs today and I've been yo-yoing in and out of the toilet most of the time. The strange thing is that my bowels seem to have a Tardis-like capacity for producing shit. I'm sure I've shat out more than I've eaten in the past 3 days, easily. Where does all that crap come from? Perhaps I've lost some not-so-vital internal organs in the process. Perhaps my appendix? Anyway, that's a little snapshot of the thoughts going through my head today. I think I may have gone slightly peculiar after all this time on the road.

Friday, October 28, 2005

The Middle Of Nowhere

I don't know what I was expecting from this remote metropolis, but it certainly wasn't the throbbing neon lights, loud music and fancy stores that greeted me. It is a thoroughly modern and cosmopolitan city, with an interesting mix of ethnic groups, not just Uighur and Han, but also Hui, Uzbek and Russian. Still, I was given one priceless picture of rurality just a while ago: walking down one of the main roads in the middle of town, blissfully uncaring of the traffic zooming past, was a farmer herding about half a dozen goats. I have no idea how he got there, or where he was going with his little troop, but it was a priceless moment for me.

Urumqi is also the political and administrative centre of Xinjiang (or, to give it its full name, Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region), which is also China's largest province by area (if it were a country it would be 17th largest in the world between Libya and Iran). The region, along with Tibet, also has an underground independence movement, although it's Tibet that seems to grab all the headlines (probably because Buddhism is more in fashion and they've got the Dalai Lama as a figurehead) nonetheless nationalist sentiment among the Uighurs runs high. The Chinese government is doing its best to counter this through several means: allowing a certain degree of autonomy (Uighur is an official language within the province and there are newspapers and TV programmes in it); flooding the place with ethnic Han Chinese to dilute the Uighur majority; rewriting history to promote Chinese nationalism; and good old-fashioned totalitarian repression. It is the last two that are the most insidious and I've had a little taste of a subtle form of both of them today. I went to the Xinjiang province museum today and they had a timeline of the history of the region. Not only were there continuous references to the "glorious motherland" and "harmony between the people" but whilst recounting the history the exhibit jumped from the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) to the Qing dynasty(1644-1911), completely skipping the 300 years of the Ming dynasty that lies in between, which, oddly enough, was the time of greatest independence for the Uighur people. I wonder whether the locals notice and what they think of it? The soft repression is happening right now at the cyber cafe. As I'm surfing I'm finding many more websites being blocked here than in the rest of the country, and most of them are very innocuous (honest!).

Tuesday, October 25, 2005

Depressed

Although Turpan and the western province of Xinjiang are politically part of China, ethnically, linguistically and culturally they are closer to the Central Asian "Stans" than the Orient. This is where the Oriental and Caucasian peoples meet and mix, a fact you can see by observing the faces of passers by on the street where the remnants of the Tocharians (a kingdom that existed in the area some 2500 years ago where they spoke a language related to German and Irish) can be seen in the occasional head of brown hair and blue eyes. The relentless march of modernisation is also held in check by the donkey carts that trot along the dusty roads and wizened old ladies sitting in doorways sorting this years raisin harvest.

During the heyday of the Silk Road the area was an important staging post for merchants as is demonstrated by the massive remains of two cities that thrived in the area before being razed by Genghis and his horde as they passed through. Again, the dry conditions have helped preserve the remains of the fragile mud-brick buildings and so you can spend hours getting lost in the labyrinth of crumbling walls and alleyways. The ruins, especially of Jiaohe, would certainly be world renowned if they weren't so inaccessible, or have so much competition from other incredible sights in China.

Sunday, October 23, 2005

Doon The Dunes

The oasis town of Dunhuang, apart from being a cozy little place with a lively market, is well situated close to several worthy sights. Indisputably top of the list are the Mogao Grottoes where, starting more than 1500 years ago, Buddhist artists carved niches and caves containing thousands of statues and religious frescoes into the sedimentary cliffs. As the oldest examples of Buddhist art in China (Buddhism arrived from the Indian subcontinent via the Silk Road) they show an intriguing blend of Chinese and Indian influences that is not found anywhere else. And although you only get to see a handful of the more than 700 grottoes the impression you're left with is still inspiring. And although the caves should be world famous for the statues and paintings alone, they have become notorious for cave number 17, also known as the library cave. About 1000 years ago the monks of the area, fearful for some reason or another, hid away a treasure trove of 50,000 scrolls and books in a secret cave which they then sealed up. The scrolls contained writings in a multitude of languages: Chinese, Tibetan, Persian, Uighur and several that are still unknown. It wasn't until 1900 that a local monk, whilst cleaning the cave, found the sealed up entrance. Such a momentous archaeological find couldn't remain secret for long and soon archaeologists from all over the world were beating a path to Dunhuang. The first to make it were the Brits, followed by the French, the Japanese, the Russians and the Americans. By the time the Yank expedition made it there the entire hoard had already been carted off abroad (apart from a few thousand pieces that the Chinese had managed to keep) and so they had to make do with removing entire chunks of wall paintings instead. Of course there is a case to be made for such actions as it is likely that they actually helped preserve the artifacts and allowed them to be studied. Nevertheless cave 17 has become something of a cause celebre here in China, much like the Elgin Marbles in Greece.

About 100km west of town are the remains of several forts and stretches of the initial, 2000 year-old, Great Wall. Despite being made of mud bricks and straw and abandoned 1000 years ago, the ruins are still in pretty good shape. Their remoteness, or perhaps the fact that they have neither been touched up or restored, makes the ruins feel as if they are removed from time altogether, existing in some sort of time stasis. I was also lucky enough to be accompanied by a Taiwanese guy called Steven who not only had a digital camera, but a laptop as well; a fact I utilised mercilessly by borrowing a great many of his pictures and adding them to my own photo album.

I had met Steven the previous day whilst traipsing around the singing sand dunes close to Dunhuang. There's a little lake hidden away in amongst the dunes and some cheeky little bugger has decided to charge $10 to have a look at it. The fact that fencing off an entire desert is impossible means that it is very easy to slip in for free, although the busloads of local tourists haven't cottoned on to that fact yet. I had a whale of a time clambering to the top of the massive dunes (not at all easy I can tell you) and then bounding down them in great leaps. It was great fun, but next time I wander off into the desert I really ought to take some water as well.

Tuesday, October 18, 2005

The End Of The Wall As We Know It

At the moment I'm in Jiayuguan, which is in a narrow stretch of land called the Hexi Corridor in Gansu province, which, I think, looks uncannily like a spaceship. The Hexi Corridor is sandwiched between the Tibetan plateau to the south and the Gobi Desert, giving the province a rather odd shape. Despite its strange geography (or rather, because of it) the area was vitally important to China in ancient times as it was the only route that could be taken by the famous Silk Road that linked China to the Middle East and Europe. And in this strategically important region Jiayuguan was the focal point, as it was here that the Great Wall ended, and although the Chinese empire stretched further west, official protection ended here. To mark the entrance to their empire in suitable style the Chinese built an impregnable fortress across the narrow valley with a wall running south (3km) to a sheer river gorge and north (6km) to a chain of mountains that line the Gobi. The starkness of the landscape also adds to the frontier atmosphere (even though the industrial monstrosities directly behind the fort try their best to do the opposite). You really get a feeling of stepping into a different country, with the added bonus of not having to go through the whole visa and border crossing rigmarole.

For those of you back home who are slightly jealous of all my travelling and have a penchant for schadenfreude I've got a little story to warm your hearts. The road from Xiahe to Jiayuguan is a long one and I had to take an overnight bus, though it seems they were scraping the bottom of the barrel when they were kitting out this one: a juddering suspension, a clapped-out engine that made the whole chassis vibrate like something out of Victoria's Secret, and, to top it all, no blankets! Luckily I still had my sleeping bag with me, even though it is just a one season one (and that season definitely ain't Winter), so I was only mildly frozen by the morning. Though the experience has finally made me take the plunge and invest in a rather fetching pair of thermal long-johns (sexy!). On top of all that everybody on the bus was smoking and consequently they all had horrible hacking, smokers' coughs, so I dubbed the journey the Emphysema Express (I even had a little song in my head to the tune of the classic Marrakech Express).

P.S. Although the Jiayuguan fort is advertised as being the end of the Great Wall, and it certainly was during the Ming and Qing dynasties (13th-20th centuries), in an earlier incarnation the Wall (circa 100AD) stretched another 500km to the west, though because this is effectively in the middle of nowhere it is more expedient from the tourism point of view to make Jiayuguan the terminus as the town has its own train station.

Sunday, October 16, 2005

Back In Tibet

Travelling in Tibet is not so much fun though. Buses only leave early in the mornings and go from one main town to another, but if you want to go further than one town in one day you're out of luck, as even if you arrive in the late morning you have to stick around until the next day to catch your onward connection. Plus Tibetans don't travel well: most of the men chain-smoke and half the bus is usually throwing up out of the windows (not fun if said people are leaning over you to reach the aforementioned window). At least you get compensated with some amazing views.

So my first proper stop after Jiuzhaigou was the town of Langmusi, which straddles the Sichuan-Gansu border. Here I almost got to witness a Tibetan sky burial, though it was called off for some reason. Sky burials are the traditional way of disposing of bodies in Tibet: the recently deceased are taken to a special place in the mountains and then the body is ceremonially sliced open, scalp to groin, and left for the vultures, who, so it is said, only take 15 minutes to leave just clean-picked bones on the ground. The reason for such a burial rite is the harsh Tibetan topography: the ground is often too hard to bury a body and wood is too scarce a commodity to be used for cremation. Although there was no burial there were plenty of bones and rags scattered about the burial ground. To see some pictures of a sky burial click here (not for the faint-hearted!).

Now I'm in Xiahe, site of one of Gelugpa Buddhism's (the main school of Tibetan Buddhism) holiest 6 lamaseries. Pilgrims come from all over the Tibetan plateau to do the kora (in Tibetan Buddhism a pilgrimage trail around a holy site, which can be a building, stupa, mountain, etc. always done clockwise, and usually three times as well, unless it's a really long kora) round the walls of the lamasery, spinning the thousands of prayer wheels as they go around the walls of the lamasery, which is almost as big as the town itself. It's very easy to get lost amid the many temples, colleges, stupas and monk's quarters; it's actually a little town all to itself. Which is all the more impressive considering that the complex was severely damaged during the Cultural Revolution. Ah yes, I said I would talk about that earlier. Well, in 1966 Chairman Mao, in his infinite wisdom, decided to rid China of the remaining "imperialists", "intellectuals" and "counter-revolutionaries", and throw off the shackles of the old world and replace them with new ones. To reach this end millions of fanatical Red Guards (young students who were completely devoted to Mao) were given the power and authority to liquidate anybody or anything deemed to belong to the old world order (paintings, statues, monasteries, musical instruments, palaces and anything else that one would consider to be of cultural value). Millions died, the country was thrown into turmoil and countless national cultural treasures were irrevocably destroyed. That's why, whilst travelling around China, you often visit sites that "were unique and amazing examples of Ming architecture", put are now little more than a pile of rubble.

But that's enough of the history lesson, I've got something much more important to impart to you dear readers today. Whilst wandering about the lamasery I've discovered that yak butter has a multitude of uses, apart from being used as a novel tea flavouring. You can make nifty candles out of it and, even more spectacular, also sculptures! there's a whole building full of yak butter statues and bas-reliefs. Neat! I also got stopped by a group of young monks, but the language barrier made communication rather difficult. In the end we did manage to find a common denominator though: football. We'd take it in turns to name a footballer and the other would give a big smile and a thumbs up when he finally deciphered who the other meant. Entertaining for a few minutes, but rather tedious after that. The contrast between the monastic life and the modern world is perfectly demonstrated as I'm writing this post in an internet cafe: about a quarter of the surfers are monks, dressed in their crimson robes, chatting away on Yahoo or playing strangely violent online games. Surreal!

Wednesday, October 12, 2005

Quantum Tourism

I'd love to say that Jiuzhaigou is a natural paradise with beautiful hiking trails, unspoilt views, crystal silence and wildlife aplenty. Unfortunately this is China, and although I know I've had a go at Chinese tourism (and tourists) before, the spectacle I experienced here just made me want to cry, pull out my hair and throttle everybody, all at the same time. Things didn't start well even before entering the park:. Arriving at Jiuzhaigou town is like driving along the Las Vegas Strip: a long row of hotels, one after another, each gaudier than its predecessor (made even more astounding by the impossibly remote location). Then, upon entering the park (entrance fee $25) you see a whole fleet of buses (ticket $11) ready to whisk you all the way to the ends of the valley. Now I'm not against buses per se, in fact it helps keep the trails less crowded and more tranquil, but because the park is such a narrow valley those of us who want to hike (i.e. are too tight to pay the exorbitant bus fare) have to do it either right alongside, or at least very close to, the road. And what with the relentless cavalcade of coaches, and the fact that they keep blaring their horns (who cares if the park is home to some of the last giant pandas in the wild), the hike quickly slips away from the desired rural idyll. Then, when you finally reach a piece of wilderness (the spot in question was called Primeval Forest), a busload of tourists rocks up and its passengers find the greatest pleasure in walking into the middle of the forest (home to the above-mentioned pandas) and screaming at the top of their lungs (nothing clever mind you, just screaming because they can).

Now I'd like to think that I'm an open-minded and tolerant person, but there can be no excuse for such behaviour. It really made me see red. And unfortunately this is the behaviour of the majority here in China; they seem incapable of appreciating nature as it is and feel an incessant need to bend it to their liking. The famous trekker's dictum of "take nothing but photos and leave nothing but footprints" is completely lost on them. So just as in quantum physics, where you cannot observe a particle without fundamentally altering its state, so the Chinese cannot go into a pretty forest without building an enormous hotel complex, complete with helipad, amusement park and nightly fireworks displays, slap-bang in the middle of it. In all the countries I've been to I haven't seen anything comparable, and despite the fact that I try to see the best in people (usually), god help the remaining (few) areas of pristine wilderness here because before long they will either disappear completely or be turned into Disneyland caricatures of what they should be.

Well, that's about enough criticism for one night, but suffice to say that if you ever do plan to visit a natural park in China: be prepared for the worst.