From Beijing I headed up to the region historically known as Manchuria. Today though in Chinese it is simply called Dongbei, or Northwest (actually, to be more accurate, Eastnorth), a far more neutral term as Manchuria is the cradle of several unhappy episodes in Chinese history: first there was the disastrous Manchu Qing dynasty that oversaw the stagnation and decline of China; and then Manchuria became the backdoor through which foreign empires, first Russia and then Japan, invaded. It's not a particularly touristy area, its major draw is the imperial mountain resort at Chengde which is popular with locals (and shows that there is a sizeable affluent middle class with disposable incomes, as the entrance ticket costs almost $20 regardless of nationality and with no reductions, even for people with fake student IDs). Even though I arrived at 8am the place was already thronged with families on weekend breaks, tour groups with matching T-shirts and baseball caps and, particularly memorable, large groups of older women doing undemanding dance routines to easy listening music. Old-timers in China are surprisingly sprightly, and it's not uncommon to see them doing tai-chi, singing karaoke or even kicking about a shuttlecock in a city park.

In the small provincial capital of Shenyang - small for China that is, it's still the size of Madrid - I spent an afternoon wandering about the city centre. Although it was the Manchu capital way back when, there is precious little remaining from its illustrious past save the old palace and a couple of tombs, the rest of the city is thoroughly new (unfortunately this is quite common for Chinese cities which lost a great deal of their long history in the disastrous Cultural Revolution). Particularly popular among the modern buildings are shopping malls. In the West I get the feeling that there is a widespread fear, or at least anxiety, about the rise of China and its new-found wealth and power. That it will somehow nefariously take over the world and overthrow the democratic ideals of the West, or some such other suitably doom-laden nonsense. Yet the reality I see on the ground is that the Chinese would rather use the wealth to go shopping and to buy Western designer brands - even in China the "made in China" mark is a symbol of poor quality and derision. There is no great conspiracy to take over the world, but simply a desire to be able to have what we have, through fair means rather than foul.

|

| Shopping in Shenyang. |

|

| Go West, for there are greater mercantile opportunities there! |

That is the realisation that is becoming more and more apparent the more I travel, the universal nature of humanity (I know it's poor writing to put a conclusion in the middle of your work - and by my ad hoc calculations I'm not yet half way through this trip). It's a thought that has become ever more present in my mind every time I spot a familiar vignette of life in unfamiliar surroundings. If that doesn't make sense I'll try and illustrate with a few examples: in a square outside a cinema in Ulaan Baatar I saw a group of concerned local teenagers accosting passersby to raise money and awareness for street children; or a Turkmen family sitting in a park having a picnic as the kids kick about a football; or a party of gays having a fun time at a club in Bishkek. All around the world people want pretty much the same things: to be able to live comfortably, to not have to worry about money, or abuse of power by authorities, for their children to have a better life, to be able to indulge every once in a while in life's little luxuries. To live a life that for us would seem rather ordinary.

|

| Luxury box of mooncakes on sale at a street stall. Mooncakes come in all shapes, sizes and prices. |

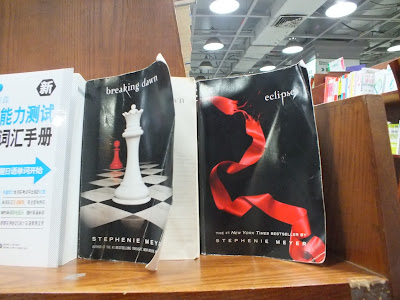

But back to Shenyang. I wanted to do a little shopping of my own. I wasn't interested in clothes, or in the stalls selling fancy boxes of mooncakes for the Moon Festival, but instead I wanted to buy a book. I wasn't too fussed which specific one, but recently I have rekindled my bookworms' hunger and have been devouring books at a prodigious rate, whatever I can get my hands on (and when you're travelling in far-flung countries the selection is often limited yet eclectic). I had the address for a bookshop that supposedly had a selection of English-language books so I set off to see what I could find to slake my literary thirst. It was fascinating just to see the strange selection of books that were on offer. There were the obligatory classics of course, with a heavy inclination towards the "chick lit" end of the scale (Bronte sisters, Jane Austen, DH Lawrence, etc.), supplemented by abridged versions for learners. All pretty standard so far. But then there was the sizeable number of collections of speeches and obscure tracts by little-known Enlightenment philosophers. Yet try as I might I couldn't find a single, contemporary novel until I finally came across two very dog-eared tomes from the Twilight saga (and the final books at that). Obviously the authorities fear the subversive nature of Jeffrey Archer and the widespread panic that would be caused by Stephen King. Instead I settled for the daddy of vampire novels to keep me company and bought a copy of Bram Stoker's Dracula to while away the train journeys.

|

| Not really much of a choice when it comes to contemporary fiction in English in China. Better to stick to the classics. |

No comments:

Post a Comment